The detective fiction formula requires there be a trail of clues for its detective to follow and solve the case. But what other clues are the authors leaving behind about the characters they harm? Does the formula necessitate that bodies are merely plot devices? Somebody has to get killed if we’re going to have a murder to solve, and from then on it’s the mystery that matters, less so the bodies themselves. But is there any room for acts of care, for these bodies to be treated with respect and mourned?

For Spring 2022, I took the English course Mad Women: Villains, Sleuths, Spies (ENGL 78100-01) with Dr. Caroline Reitz, in which we examined detective and crime fiction texts and media from the Victorian period to the present day that deal with depictions of female madness (anger and insanity).

One of the texts for this course was Lady Audley’s Secret by Mary Elizabeth Braddon. After reading it, I could not stop thinking about Matlida Plowson, the consumptive girl who is paid to take Helen Talboys name in death and so help Helen prevent her first husband from messing up her new life as Lady Audley. The deal is struck with Plowson’s mother, so we never even know how she feels about spending eternity buried in a grave under someone else’s name. This fraud–more so than the abandonment of her child and multiple attempted murders–is the act committed by Lady Audley that I can’t get over.

Soon after in the semester we read The Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler, in which detective Philip Marlowe–among other things–solves the mystery of what happens to Rusty Regan, the son-in-law of his very wealthy client. He was killed in an oil field and his body disappeared by some goons for hire. Another person essentially erased in death.

This got me wondering more about what death looks like across course syllabus. In a class about crime fiction, death features prominently and the bodies certainly pile up from week to week. But the deaths are not all the same, nor are the victims’ bodies all treated the same. Some deaths are more brutal than others; some bodies are treated with more care than others, and some even get funerals. I found myself asking, why are the different bodies treated the way they are? To explore answers to this question, I’ve created a chart visualizing the treatment of the bodies.

About the Visualization

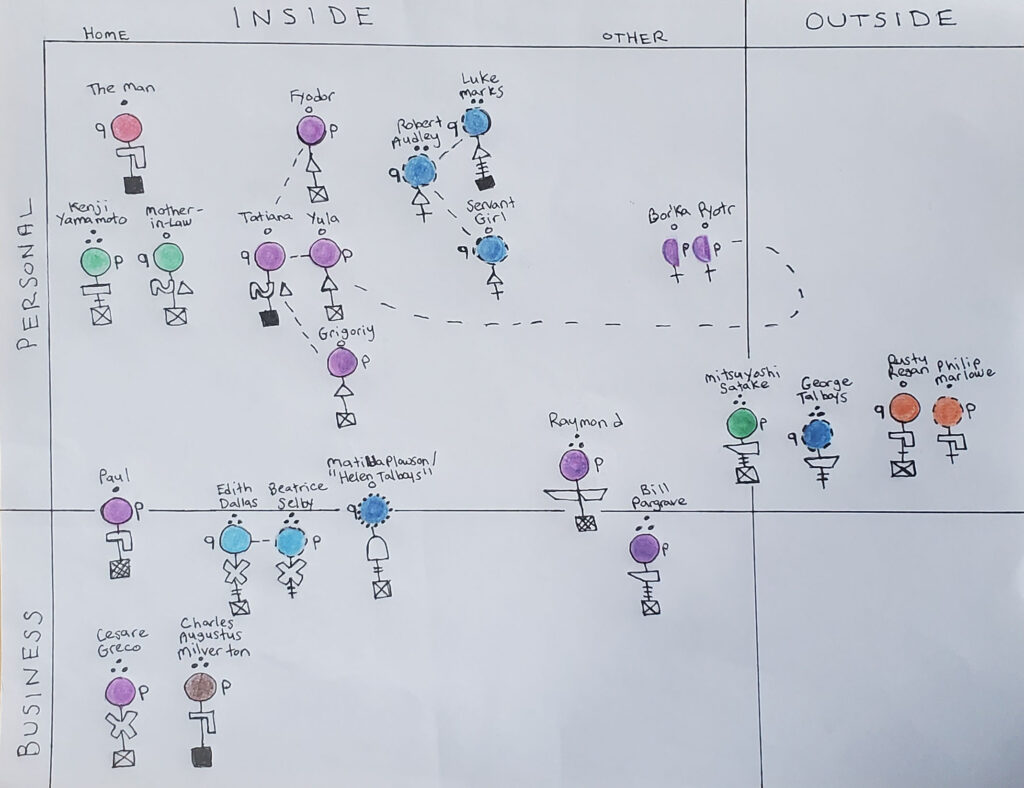

As I began planning this project and wondering how I could visualize it, I came up with a grid structure. I was so struck by Rusty and George being killed (or almost killed) in outside spaces that I wanted to compare where the other murders and attempted murders took place: inside or outside. Many more incidents occurred inside than outside, so the inside portion of the grid is much larger than the outside portion. Even within my “inside” designation, I was finding myself ranking them based on whether people were inside their homes, others homes, or other types of inside spaces (e.g., inn, hotel, nightclub), so I tried to think of inside along a spectrum from home on the left to other on the right. I was also very interested in why these characters were killed, for personal or business reasons. As such, I created quadrants: inside versus outside along the horizontal axis and personal versus business along the vertical axis.

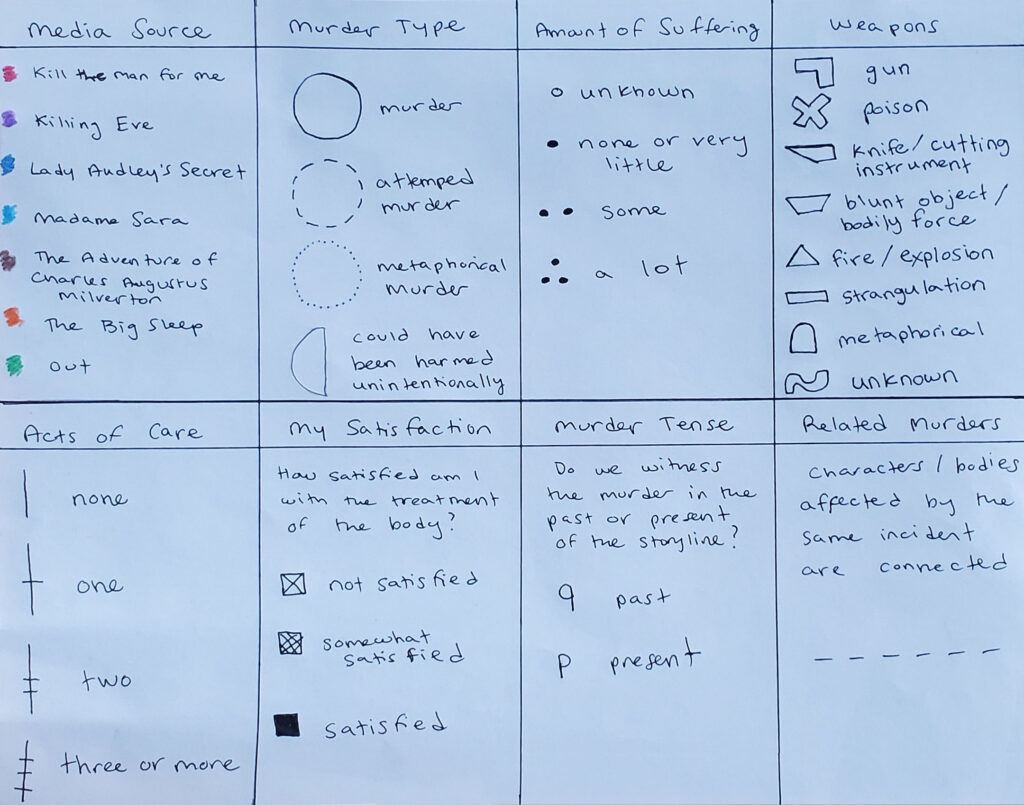

Each plot on the chart represents one person (they’re names appear above each plot). The circle representing them is color-coded to indicate which media source from the syllabus they appeared in: red for “Kill the Man for Me” by Mary Wings; purple for the TV show Killing Eve; dark blue for Lady Audley’s Secret by Mary Elizabeth Braddon; light blue for “Madame Sara” by L.T. Meade and Robert Eustace; “The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton” by Arthur Conan Doyle; orange for The Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler; and green for Out by Natsuo Kirino. The type of outline around the circle indicates whether they were murdered (full circle), almost murdered (attempted murder, dashed outline), murdered in the metaphorical sense (dotted outline), or whether they may have been harmed unintentionally in an incident that killed other characters (half circle, no outline). Above the circles I drew dots corresponding to how much I think the character suffered during the incident: one open dot indicates I didn’t have enough context clues to guess how much suffering there was; one filled dot means I think they suffered very little, or not at all; two filled dots means I think they definitely experienced some suffering; three filled dots means I think they experienced a lot of suffering. To the left or right of each circle is a backward or forward “p” indicating whether the viewer/reader witnesses the murder in the past or present, respectively, within the storyline. Below each circle is at least one shape indicating the method in which the character was killed: an angular shape for gun; an x shape for poison; a quadrangle with a point for a knife or cutting instrument; a trapezoid for blunt object or bodily force; a triangle for fire or explosion; a skinny rectangle for strangulation; a tombstone shape for metaphorical murder; and a squiggle shape when the cause of death is not known.

The next two categories I included in my data are a bit more subjective. I tried to count whether the characters experience any acts of care in the moments leading up to and shortly after their murder/attempted murder. For acts of care before death, I included such things as whether a doctor was called or there was any other attempt to save the life (either by themselves or from others); after death, I counted any attempts at memorialization (e.g., prayers, funerals) and declarations from other characters to solve the murder or seek justice as acts of care. I plotted the acts of care on a vertical line extending below the weapon shape: no hash marks on this line mean no acts of care are indicated; one hash mark indicates one act of care; two hash marks indicates two acts of care; and three hash marks indicates three or more acts of care. Below this line is a box where I indicate whether I am satisfied with the treatment of the body. I only included boxes for characters who actually died, so the characters who survived the murder attempts do not have a box. A box with an x in it means that I was not satisfied with the treatment of the body; a box with latticing in it means I was somewhat satisfied with the treatment of the body; a filled in box means I was satisfied with the treatment of the body.

Lastly, I wanted to indicate when a mass murder/attempted murder incident took place, so I’ve connected characters who were affected by the same incident with a dashed line.

The most revealing part of this visualization, for me, is the seemingly randomness of my ratings of satisfaction with the treatment of the bodies. There are bodies who received many acts of care, but I was still not satisfied with their treatment. For Bill Pargrave from Killing Eve, even though he’s received some of the most acts of care in my dataset, I still was not satisfied because his death felt unjust and a bit contrived–the writers setting him up as an important character to kill off early in the first season to show us how high the stakes are. MI6 also keeps the particulars of his death secret from his family, and while I did include that as one of his acts of care as it could have been done to protect his family, his family not knowing the truth also feels unjust. Mitsuyoshi Satake from Out also received multiple acts of care, but I was not satisfied with the treatment of his body. In his case, it was for completely opposite reasons. He was so monstrous and his acts of violence so extreme and vile that I’m disgusted his final victim actually mourns his death and is remorseful for killing him. For the other more evil characters in my dataset–The Man from “Kill the Man for Me,” Tatiana from Killing Eve, and Charles Augustus Milverton from his eponymous story–I indicated complete satisfaction with the treatment of their bodies even though they received no acts of care as they are set up in their storylines to be so awful that it’s almost impossible not to root for their deaths.

I also indicated my dissatisfaction with the treatment of bodies for characters whose murders seemed very unjust. Even though Tatiana was shown to be very cruel and potentially psychopathic, the murder of the rest of the members of her household was so unjust and literally overkill. Villanelle’s action here is so reckless I even felt compelled to include the two of her brothers she spares from the incident on the chart. She knows her one brother Pyotr sleeps in the barn, and she sets an alarm for her half-brother Bor’ka and sends him out to the barn to retrieve money to see his favorite musician, but we never see Villanelle ensure either of them is out in the barn, nor does her explosion seem to be so precise that she could have known with much certainty that the alarm was set for the correct time to spare Bor’ka or that he’d actually go outside in the middle of the night. And surviving the blast will likely cause them a lot of emotional harm, though we never see them again to know for sure (at least not as of the end of Season 3). And we don’t know how efficient her explosion was–do the other members of the household die right away? Or do they die from burns and/or smoke inhalation? For these reasons I’m not satisfied with the treatment of these bodies.

Given that my lack of satisfaction in the treatment of Matilda Plowson and Rusty Regan were the impetus behind this project, they are plotted as such. Even though Matilda was dying anyway and may have even experienced a better end of life than she would have previously with her own family (receiving multiple doctor visits, having a proper burial), we don’t ever know how much she consented in all of this. The only act of care I indicate for Rusty is Marlowe searching for him, but he’s searching for him at the request of General Sternwood, and Sternwood is never told what happened to him. Marlowe uses his knowledge of the crime to blackmail Vivian Sternwood into having her sister Carmen put away (presumably in some type of hospital/asylum) where she can’t hurt anyone anymore, but it means their father–the only person who seems to care about Rusty–will never know what happened to him. And Carmen seems to be skirting the justice system; it’s unclear even whether she really will be unable to harm more people in the future.

From Out, I’ve also plotted my dissatisfaction with the treatment of the other two murders in my dataset: Kenji Yamamoto by his wife Yayoi and the unnamed mother-in-law of Yoshi Azuma. Both of these characters are depicted as treating their attackers very poorly–Kenji physically abuses his wife and squanders all of their savings and the mother-in-law is nothing but verbally and emotionally abusive to Yoshi. But the dismemberment of Kenji’s body and the fact that the mother-in-law may have been burned alive (we don’t know for certain whether she was dead before or after Yoshi seems to have set her home on fire) are so horrific that again these feel like overkill.

In this dataset overall, I was generally not satisfied with the treatment of these bodies. Close to half (10 out of 24) receive no acts of care; and many of them suffer at least somewhat in their deaths (11 out of 24 have two or three dots above their circles, and this could be higher given that I didn’t have enough context to guess the suffering of 10 others).

Data and Design Decisions

This project was very much inspired by Dear Data. I knew that I would not be able to convey this many data points in one visualization without drawing it by hand. It also felt appropriate as much of this data is based on how I was feeling as I witnessed these murders and attempted murders and as we discussed them in class.

There were so many murders in the syllabus, I decided to narrow them down to just those committed by women. Given my fascination with Lady Audley’s Secret–and that there are technically no actual murders in it–I expanded my dataset to include attempted murders. George is presumed dead for much of the book, so I knew I wanted to include him. This meant I needed to also include attempted murder of Robert Audley by Lady Audley, as well as the two people in the inn with him at the time she set the fire: Luke Marks and an unnamed servant girl. Even though Luke eventually dies, the book is adamant that it was not because of the fire. Perhaps this is me applying a modern-day Law & Order type lens, but given that he was relatively OK before the fire and then on his deathbed after the fire, it’s very hard to believe the fire was not at least a contributing factor to his death. This is why his circle is drawn as a half solid line and half dashed line. Matilda was not murdered, but in burying her body under Lady Audley’s previous name, Helen Talboys, Lady Audley is metaphorically killing herself and also erasing Matilda’s existence, which is why I created the metaphorical murder and weapon in the plot.

Even having narrowed the dataset to murders committed by women, making this project not just about Killing Eve was challenging. Almost every murder in the show is committed by a woman, and there is often more than one murder in an episode, and at the time I began this project there were 24 episodes. I included Eve’s killing of Raymond, Villanelle’s handler, and Carolyn’s killing of Paul, her boss, so it wouldn’t just be about Villanelle killing people. For Villanelle, I tried to collect a representative sampling of the murders she commits: murders related to her job and murders she commits outside the scope of her job. I originally was going to exclude any contract kills for her because I thought, it’s just her job, but Dr. Reitz pointed out that it being her job doesn’t make much difference to the person who’s being murdered. So for her, I chose a contract kill (Cesare Greco, who is poisoned via hairpin through the eye), her killing Bill while he was pursing her case, and her killing her mother and other members of her family. Even though I included attempted murders in my dataset, I ultimately left out Eve stabbing Villanelle and Villanelle shooting Eve. Given how complicated their relationship is, it’s hard to know whether they were actually trying to kill one another–if Villanelle wanted Eve dead, wouldn’t she be dead? These two incidents opened up too many cans of worms for me, so I’ve left them out (at least in this iteration–I could remake this whole project just with the murders in this series perhaps).

Initially I thought that the divide between inside and outside would be relatively straight forward. But then I considered Satake. He and Masako are technically inside an old factory building, but it’s so decrepit that it is practically no different from being outside in terms of exposure to the elements; this is why I’ve placed him along the line. Given how many murders took place inside, I also wanted to try and make some distinctions in this half. I think of home as being the “most” inside, and then other insides like an inn (Robert, Luke, servant girl), a hotel hallway (Raymond), and a night club (Bill) as less inside compared with home. Many of the murders took place in the victim’s home, but I couldn’t layer them all on top of one another, so the movement across this axis isn’t quite as precise as I’d like it to be. There was also my wanting to include Bor’ka and Pyotr, and technically they are inside when the explosion takes place, but they go outside and then to a different inside space (a barn) from the inside where their family is killed, which I’ve tried to indicate with the dashed line that connects them to Tatiana and the rest of their family.

In terms of motive, the distinctions were a bit murky. In order to foreground the bodies rather than the solving of the murder (which focuses on the murderer), I tried to assign these motives from the victims’ point of view. For example, the unnamed woman who murders Milverton is very much motivated by how he ruined her life (personal), but ruining people’s lives is the nature of his business, so I plotted him in the business half of the grid. Bill is pursuing Villanelle for work when she murders him. Raymond is sent to kill Villanelle when Eve steps in; it’s a bit of self-defense, but it’s also close to business as Eve is there as part of her job, which is why it is close to the line. Paul is riding the line because Carolyn says it’s in retribution for the death of her son Kenny, but she also says something to the effect of the personal being business and vice versa. Similarly Matilda is on the line as she is erased as part of a financial transaction. George is near the line as marriage is a personal but also a legal matter, which puts it close to business for me; furthermore, he abandoned Helen Talboys/Lady Audley to build a new business and make the money he promised her, which is a large part of why she does everything she does. Satake is also close to this line as he initially pursues his killer as he blames the group for ruining his business, but I kept him on the personal side as he singles out Masako for personal reasons (he is obsessed with her and recreating his first murder through her).

For acts of care, I was originally just going to include practices relating to death, like funerals and other types of memorialization. But then I noticed there were a lot of people in my dataset being saved, like Beatrice Selby, Luke, and the servant girl, and I noticed also there are several people who actually save themselves (Robert saving himself and others from the fire; George climbing up out of the well; Philip Marlowe filling Carmen’s gun with blanks as he assumed she’d shoot at him), and I thought that these most certainly are acts of care–you can care for yourself as well as others.

Similarly for suffering, I was originally only going to include physical suffering. But as I reread “Madame Sara” the text is insistent that Beatrice will never be the same/recover from the incident, and I thought surely emotional suffering is at least as important as physical suffering.

When I began doodling and trying to visualize how this would all lay out, I original just thought of the circles as being heads, and then in a class discussion when I presented a draft of this project, it was suggested that perhaps all of the data/parts of each plot could resemble a person, like in the game hangman, which I really liked. So I just kept trying to come up with different sets shapes/designs for the different categories, and assembling them together in a way that I thought vaguely resembled a body. For the weapons, I drew shapes that I thought were somewhat representative of the weapon’s shape in real life. In hindsight the blunt object/bodily force shape and the knife/cutting instrument shape are bit too close to one another, especially as I combined them for Raymond’s murder (he was killed with an axe). On a similar note, I chose colors based on colored pencils I had on hand, but I wish that the two blue colors would have been more distinct. In a future iteration, I will pick all colors that are more easily distinguished from one another.

Next Steps

For my next steps, I plan to turn this visualization into a storymap using StoryMap JS. I’m particularly inspired by this project that has turned Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights into a storymap. I want to be able to view the bodies in the visualization in more detail and have accompanying text that explains a bit about the media sources and why I visualized the murders the way I did. While there will be an overall narrative that I create, I also like that the map will allow users to access the data points in a different order if they so choose.

Thank Yous

I want to give a huge thank you to Dr. Reitz who helped me realize this project and let me bounce all my ideas off her; and of course without her syllabus none of this would have been possible. She also came up with the clever title. And I also want to thank all of my classmates as this project would also not have been possible without our very fruitful and thought-provoking conversations about the course materials.